Women Scientists in Literature: Telling Stories to Repair the Matilda Effect

When novels, essays and graphic non-fiction repair forgetting: literature restores names and evidence to discoveries made by women. A powerful lever against the Matilda Effect.

Literature has a unique power: it creates lasting narratives. When it takes up the stories of women scientists, it does more than "tell lives": it reconstructs the files of credit, stages the evidence, highlights laboratories and archives, and makes visible trajectories that have long been relegated to the margins. This is precisely where literature becomes a tool against the Matilda Effect: it corrects the blind spots of textbooks, challenges the habit of crediting a single "great man" for work produced by mixed teams, and restores women authors to the center of discoveries.

Aucun homme ne choisit le mal pour le mal, il le confond seulement avec le bonheur, le bien qu'il cherche.

In fiction, novelists revive the lives of researchers whose memory has been shaken. These narratives do more than portray heroines: they show the work — notebooks, experiments, controversies and belated recognition. By revealing the backstage of knowledge, fiction exposes the forces behind invisibilization: institutional silences, forgotten signatures and media accounts that favor masculine exception at the expense of collaborative chains. It offers readers complex characters — neither frozen icons nor secondary silhouettes — and puts the scientific method back at the heart of action.

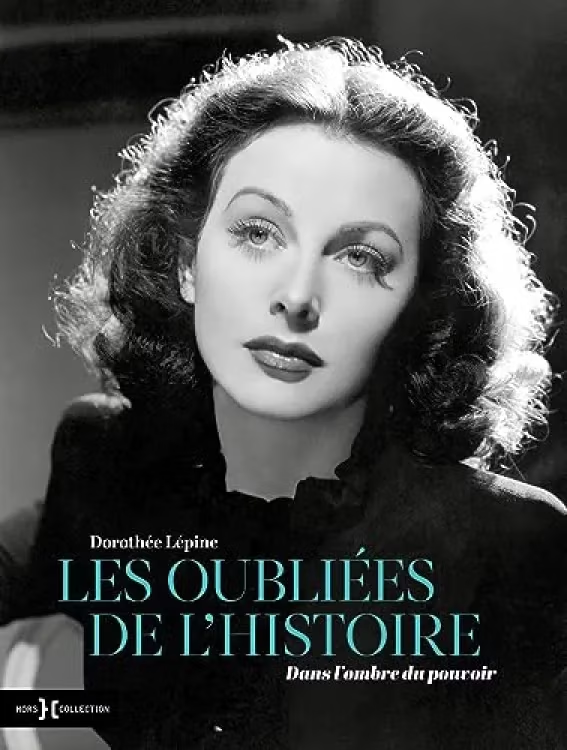

On the documentary and biographical side, authors reassess credit by relying on archives. Letters, dated notes and co-authored articles reveal editorial negotiations, academy refusals and juries that hesitate to name the right person. This precise form of writing builds a counter-narrative that does not seek to replace one pantheon with another but to document who did what, when and how. From Rosalind Franklin to Lise Meitner, from Mileva Marić to Hedy Lamarr, these works show that invisibilization is not anecdotal but a cultural fold that evidence and narrative can undo.

Although varied, the twists of life are less changeable than human feelings.

Documentary graphic novels occupy a special place. They combine rigorous sourcing with visual power: diagrams, facsimiles and lab scenes. Through this language, figures become immediately accessible to a wide audience. When a page juxtaposes a portrait and a notebook excerpt, the link between idea and author becomes indisputable. Graphic non-fiction thus strengthens the pedagogy of credit: it shows, cites, contextualizes and invites verification.

These three families of works naturally converse with other pages on your site. The film about Marie Curie has already highlighted the fragility of credit and the power of evidence — a useful bridge to biographies and graphic non-fiction that lay out, more coldly, the stages of a discovery. The article on Ada Lovelace reminds us that modern algorithmics was born from an intuition written down in technical notes: a direct echo with books that reconstruct general programmability and the historiographic debates around her role. The reference volume devoted to the "forgotten" finally offers a transversal mapping, ideal for creating internal links and enriching your sidebars.

Was Man then at once so powerful, so virtuous and magnificent, and, on the other hand, so vicious and so base?

However, vigilance is required: literature can — by its taste for narrative — simplify, condense or merge characters. The risk would be to fabricate a new myth that erases the complexity of collaborations. Good practice for an educational site is to make novels, essays and archives converse: cite works, specify what is interpretative, and link to source documents when possible. This critical framework avoids replacing one form of invisibilization with another.

Beyond symbolic repair, these books have a concrete effect: they provide identifiable role models. Seeing researchers in action, understanding their publication strategies, and observing how they kept notebooks or defended their results gives readers practical gestures to reproduce. Literature thus becomes a method: attribute precisely, document in advance, and consider visibility as a component of scientific truth.

La vie est tenace, et persiste le plus longtemps quand elle est l'objet de la haine la plus profonde.

As part of your site's editorial continuity, this article is conceived as an entry point. It invites readers to navigate to the Ada Lovelace page (for the birth of the algorithm and the question of credit), to the analysis of the film "Radioactive" (for staging biases and institutional corrections), and to the presentation of the "Forgotten Women of History" (as a case-library). Together, these contents weave a single idea: to tell is already to attribute; to attribute is already to repair the Matilda Effect.