Ada Lovelace's Note G: how her "first program" works

Ada Lovelace's Note G explains, in 1843, how to make a machine execute a sequence of instructions. It is the concrete birth of the algorithm... before the computer.

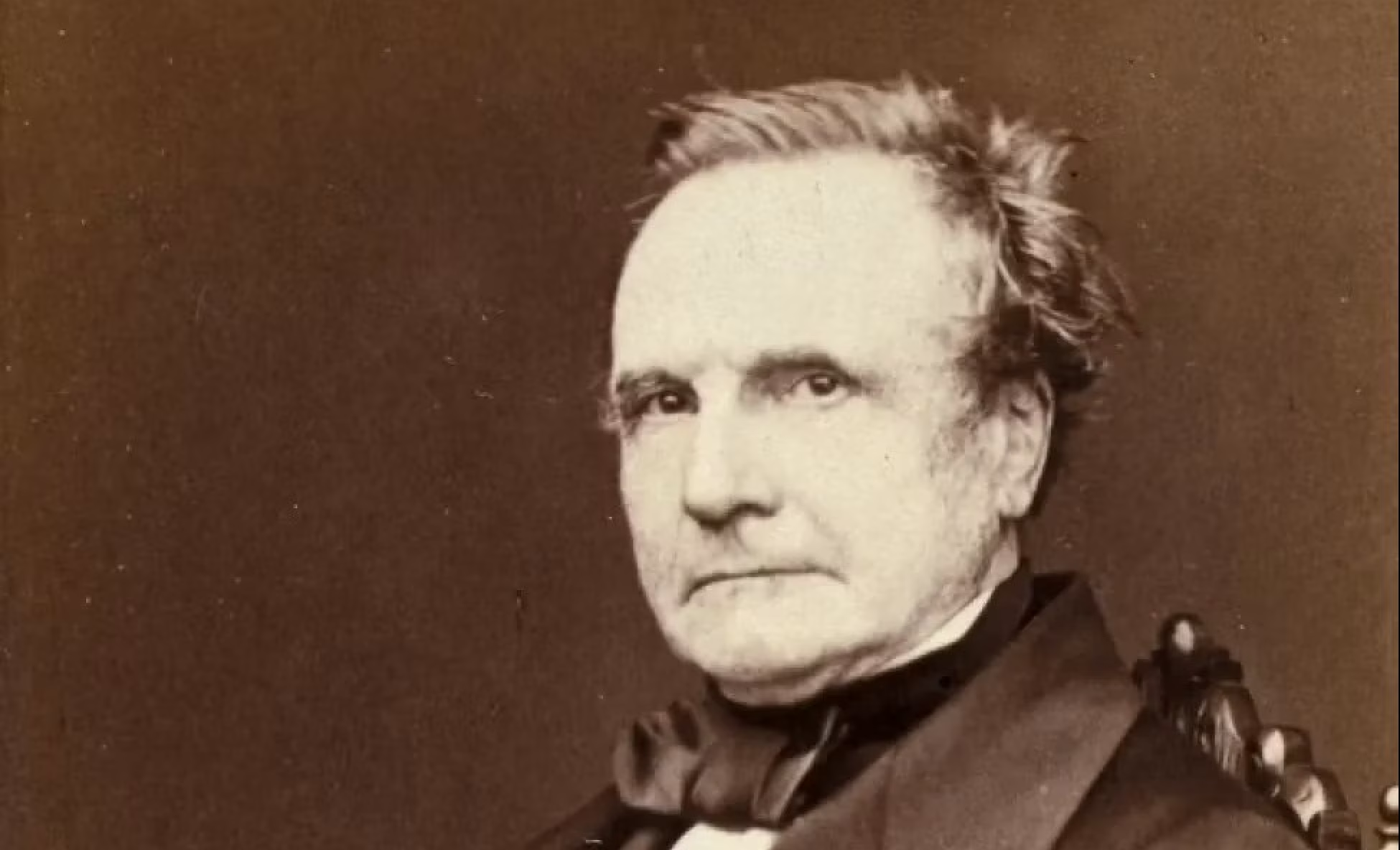

To understand Note G, we must go back to 1843. Ada Lovelace translated an article by the mathematician Luigi Menabrea about the Analytical Engine imagined by Charles Babbage, then added long personal notes. The most famous, called "G", lays out a detailed plan for making the machine compute a sequence of specific numbers, the Bernoulli numbers. This plan is often presented as one of the first published "programs": not code as we write it today, but a sequence of operations formulated with a rigor that anticipates modern algorithmic thinking.

Lovelace begins by clarifying what the Analytical Engine would, in principle, do. The machine has a "mill" where operations take place and a "store" where intermediate values are kept. Instructions and data are fed by punched cards, modeled on Jacquard looms. This separation between the place of computation and the place of memory, and the idea of a program written externally, represent a conceptual revolution: they make it possible to imagine a general-purpose machine configurable at will.

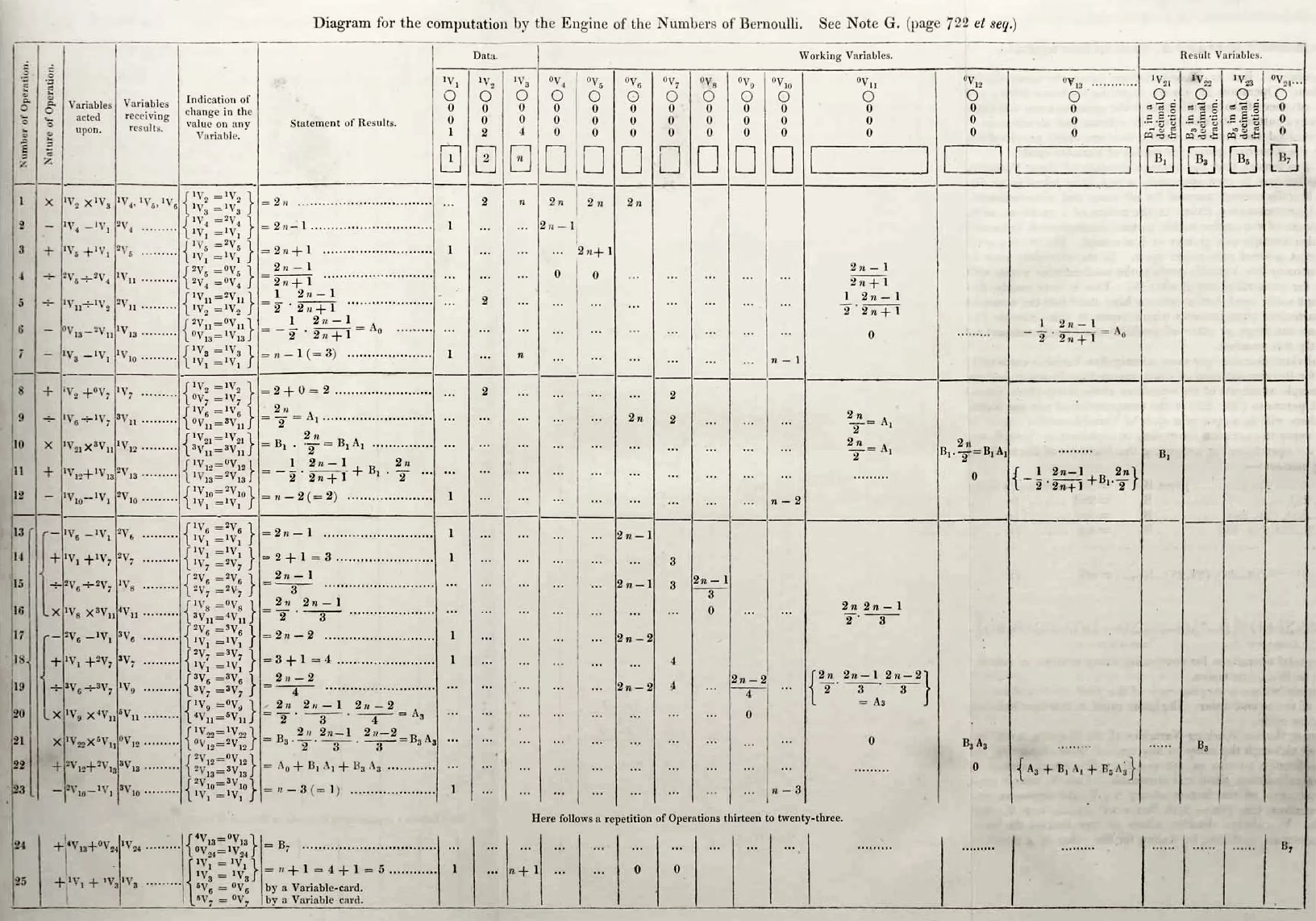

At the heart of Note G is a large operation table. From one column to the next, Ada specifies which quantities the machine should take from the store, which operation to perform in the mill, where to place the result and how to reuse it afterwards. It is not a narrative but a method: prepare initial values, transform them according to rules, and at each step control what must be stored or erased. Reading the table reveals a core idea of computer science: a program is an explicit recipe that breaks a problem into simple, ordered and traceable actions.

My mathematical work involves considerable imagination.

Why the Bernoulli numbers? Because they make an excellent test. These mathematical constants appear in many analytical formulas (power sums, series expansions) and are suitable for recurrent calculations. By choosing this example, Ada shows how a machine can handle a computation that is neither trivial nor purely mechanical by combining additions, multiplications and repeated substitutions. She also introduces the principle of iteration: the same portion of the "plan" is run several times with updated values, much like today's loops. You can sense the emergence of flow control: the sequence of operations is not a fixed block but adapts according to the current state of the variables.

What strikes the reader is how Note G stages traceability. Every provisional result is named, stored and retrieved. It becomes clear that the important thing is not just obtaining a final number but being able to trace the path that leads to it. This is the very logic of modern debugging: if the result is wrong, you trace back the chain, inspect stored states and correct the faulty rule. In 1843, Ada already formalized this engineer's reflex: a good program is one whose every transition can be explained afterwards.

This brain of mine is something more than merely mortal, as time will show.

The reach of Note G goes beyond its example. Implicitly, Ada proposes a bold thesis: if you can represent something with symbols, then a machine can, in principle, manipulate it. Numbers are only one case. Music, text and shapes can become computable once you know how to encode them. This intuition paves the way for the idea of a universal computer, a symbolic tool capable of processing very different structures — an idea that resonates with our contemporary software, from text processing to synthesizers, from computed images to generative AI.

The coherence with the Matilda effect is about credit. For a long time, Ada's contribution was presented as a simple translation with commentary, whereas Note G represents a genuine conceptual contribution: a description of an execution plan, the memory–computation articulation, iteration and explicit state handling. The fact that the Analytical Engine was never built was used to downplay this work, as if an idea only exists with its prototype. The value of Note G is precisely to show that programmability is a matter of method and representation, not merely available hardware. Telling this text clearly helps repair part of its invisibilization.

For me, religion is science and science is religion.

To popularize Note G for a modern audience, one can read it as a well-written recipe. The ingredients are the initial values, the cooking plan is the operation table, the kitchen is the mill and the pantry is the store. You follow the recipe by checking at each step what must be mixed, kept, discarded or put aside for later. If the cake doesn't rise, you don't curse the flour: you reread the recipe, correct the sequence and adjust the quantities. This is the methodical pedagogy Ada left behind: learning to speak to a machine is first learning to write instructions that are clear, traceable and reusable.

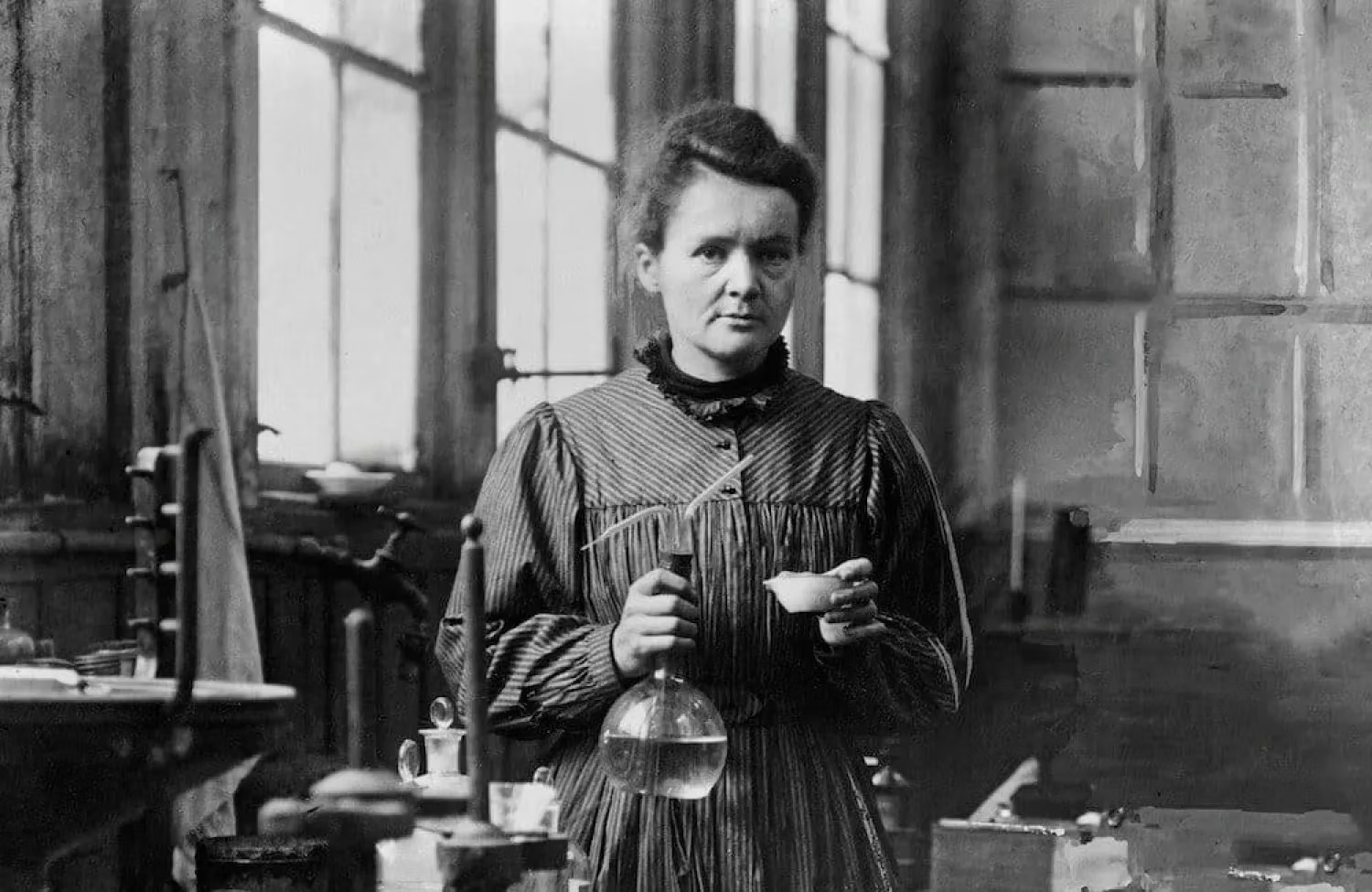

Ultimately, Note G fits naturally into the architecture of your other articles. With the analysis of "Radioactive", we saw how credit can falter when evidence is not made explicit; with "The Forgotten Women of History", we linked cases of invisibilization to concrete acts of repair. Here, Ada Lovelace shows how to produce an operational proof: a plan, states and an execution. It is the technical building block that was missing to understand, from within, what a program is and why correctly attributing its authorship matters as much as the result it produces.