Ada Lovelace: the First Computer Programmer

Visionary yet long minimized: Ada Lovelace imagined the algorithm and a general machine, then faced invisibilization — the Matilda Effect, in plain terms.

To tell the story of Ada Lovelace, we must hold together two threads: a technical intuition of unsettling modernity and a public narrative that long muted her achievements. Born in 1815, the daughter of poet Lord Byron and Annabella Milbanke, Ada grew up between the music of words and the rigor of mathematics. Influenced by scholars like Mary Somerville, she learned to think of ideas as manipulable structures. This way of inhabiting both language and calculation led her, before many others, to see that a machine could execute abstract instructions.

My mathematical work involves considerable imagination.

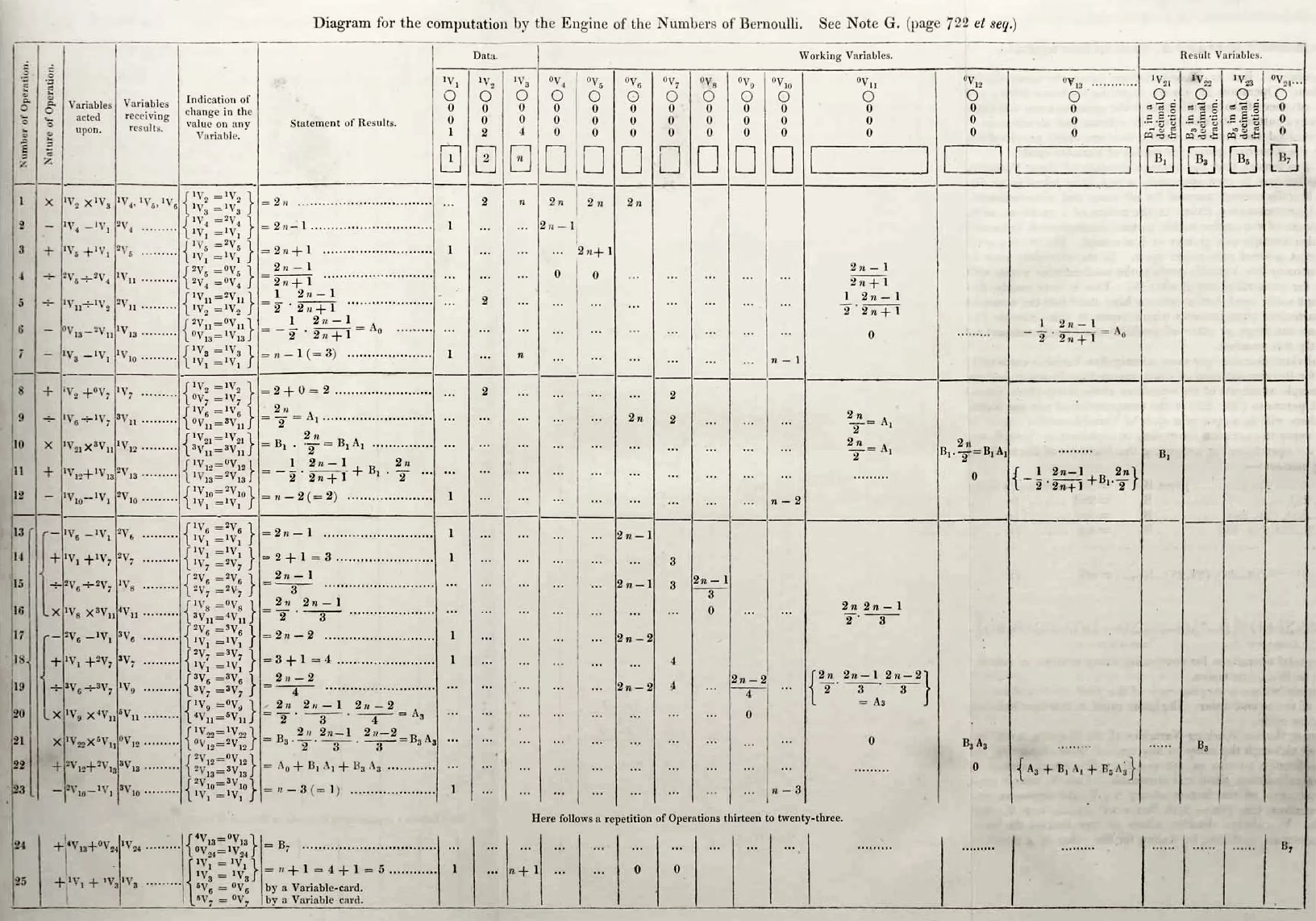

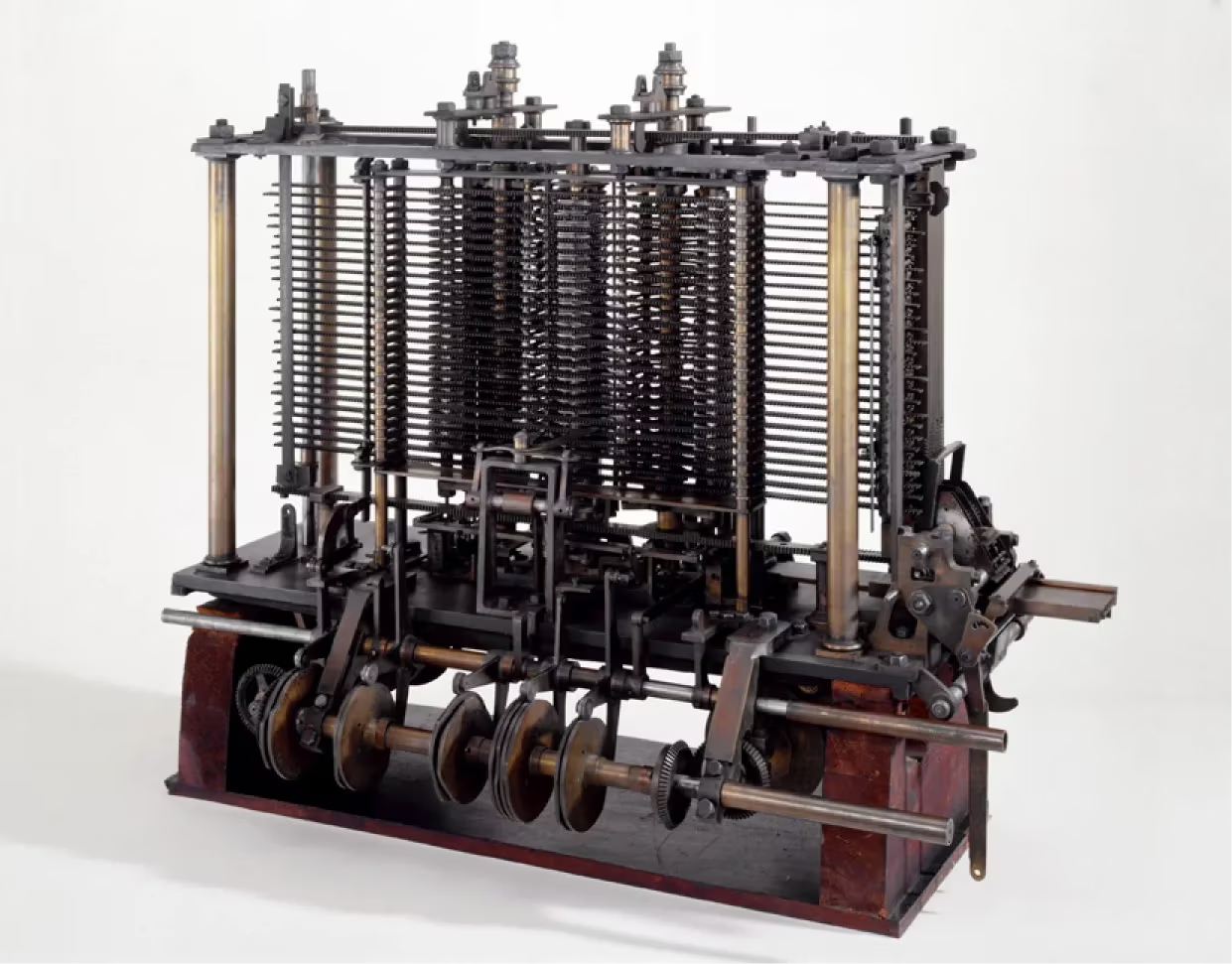

Meeting Charles Babbage opened the field: the Analytical Engine, still theoretical, promised to separate the place of calculation (the “mill”) from memory (the “store”) and to introduce programming via punched cards. In 1843 Ada translated a paper by mathematician Luigi Menabrea and enriched it with long Notes. She laid out an execution plan for the machine to compute the Bernoulli numbers and, above all, formalized what we now call an algorithm: a sequence of finite, ordered and traceable operations in which intermediate results are named, stored and resumed. It is not “code” in the modern sense, but it is its grammar.

In the 1830s, Ada discovered Babbage's projects: first the difference engine, then, above all, the Analytical Engine—a punched-card machine capable, in principle, of chaining varied operations. In 1843 Ada translated into English an article by Luigi Menabrea on the Analytical Engine and supplemented it with personal Notes much longer than the original text. These Notes do more than popularize: they broaden the frame. Ada explains how to decompose a problem into instruction sequences, anticipating modern programming and the idea of a general-purpose machine configurable by programs.

The intellectual, the moral and the religious seem to me all naturally linked and chained into one great and harmonious whole.

The scope of this vision goes beyond numerical calculation. Ada asserted a radical idea for her century: if symbols can be encoded, a machine can, in principle, manipulate more than numbers. Music, text, figures—any form that can be represented could become the object of mechanical processing. This intuition foreshadows not only the programmable computer but also proposes a cultural definition of computing as the science of representations, where one composes, transforms and orchestrates symbols.

It is precisely because the contribution is conceptual, embedded in a collective project and within a machine never built, that it was long minimized in mainstream narratives. The Matilda Effect, coined by historian Margaret W. Rossiter, describes the tendency to minimize or reassign women's contributions. In Ada's case, it appears in Babbage's shadow, the reduction of her role to an industrious “translator,” and the suspicion around an invention without a prototype. The social mechanics are familiar: we celebrate visible “genius,” naturalize the assistant, and hesitate to recognize an intellectual parentage when it disrupts expected role orders.

Twentieth- and twenty-first-century historiographical debates do not all sing the same tune: some stress the limits of the device proposed in the Notes, while others reassess their foundational value. This debate does not negate a robust fact: Ada established a method. She described how a machine could be driven by a plan, articulated memory and calculation, conceived iteration, and made execution explainable afterwards. In contemporary terms, she set criteria of readability and traceability that make a good program: one understands “how” the result is obtained, not only “that” it is obtained.

This brain that is mine is something more than merely mortal, as time will show.

Viewed in the context of this site, Ada's story naturally connects with the other pages. The analysis of Radioactive showed how credit can falter when evidence is not explicit; the presentation of "The Forgotten Women of History" mapped cases of invisibility across the arts, sciences and politics; and the exposition of the Note G detailed the inner workings of a "first program." Ada thus becomes the axis linking concept, narrative and method: she gives a face to programmability, a language to discuss it, and a warning about the fragility of credit when one confuses author and executor, prototype and idea.

Her legacy today is not merely symbolic. It takes the form of a professional reflex: document, name and attribute. A readable program is a plan that reveals its states, transitions and dependencies—exactly what Ada tried to write down. An equitable project is a way of working where people sign appropriately, archive steps, and make visible the ecologies of knowledge rather than collapsing everything onto a solitary figure. In this sense, telling Ada's story is learning to work better.

For me, religion is science and science is religion.

If Ada Lovelace has long seemed to occupy only a romantic margin of the history of technology, it is because our narratives preferred completed artifacts over processes, built machines over execution plans, and single figures over collaborations. Returning to her Notes shifts the center: it shows that computing is born of a writing gesture, that ideas exist before their artifacts, and that credit, if not maintained by method, disappears. Repairing it means encouraging programming, publishing and transmission—and writing history at the precise pace of those who make it.